How To Make Square Slot In Wood

- How To Make Square Slot In Wood Dowels

- How To Make Square Slot In Wood Lathe

- How To Make Square Slot In Wood Floors

Square Drive Screws are designed for use in furniture manufacturing operations and other demanding industries using hardwoods and other “tough” materials. “Drywall” screws are made of hardened, brittle steel and will often snap under the loads applied to drive them in joining two pieces of wood. How to Cut Slots With a Table Saw. Slots or channels cut into wood more commonly are referred to as dadoes. Slots, channels or dadoes typically are used to create stable, tight-fitting joints on. In woodworking a slot is a channel usually made to receive another piece. It is either designed to be a tight fit to hold something together like shelving or T&G flooring, or a sliding fit to permit things to move. A little research on vocabulary will tell us that a dado is a slot cut across the grain of the wood whereas a groove is a slot cut with the grain.Wood on wood sliding fits often.

Types of screws (and when to use them!)

If you’ve ever been to the fasteners section of a hardware store of home center you know how intimidating this experience can be. You may only need a few screws, but what kind should you get? There a bazillion different kinds of screws and there is no way I can cover them all, so I’ll will give you an overview of the most common types of screws and what you will need for woodworking.

What types of screws should you use in your projects?

For woodworking you can narrow it down to just a few choices. Here are my bottom line recommendations; the best screws for woodworkers.

- I highly recommend usingpremium or multi-purpose screws, such as Spax, GRK or Hillman.

- Get flat headed screws, the ones with the tapered heads for countersinking.

- If you can, use square or star drives. They work better and will save you a lot of frustration.

- The most common screws I use and like to keep on hand at all times in my shop are #8 1-¼” star head screws.

These are the most commonly used wood screws in my shop.

Why use screws?

I want to point out that I don’t really use a lot of screws in woodworking. Usually I use wood glue, which is stronger and leaves no visible fasteners. The downsides to glue are that you have to wait for it to dry and once you’ve assembled something, you can’t take it apart.

I often use screws for shop projects and jigs. With these, I’m not concerned about the appearance as much and love the time-savings screws give me.

Screws are also used to hold things together where expansion and contraction of the wood can be an issue. A common use is to attach a tabletop to a base. The screws will be set into a slot, allowing the wood to move as humidity changes.

For some projects that are sort of in the middle ground between making an heirloom dresser and a workbench, I like to use pocket screws. They are great for making cabinets and other casework. They make assembling these types of projects, say a bedframe, much easier and quicker. And of course, you want to position the pocket holes on the undersides or back of projects where they won’t be visible. Learn the basics of pocket hole joinery.

What’s the difference between a screw and a bolt?

There is no agreement on this, but personally, I view a bolt as a fastener that goes all the way through two material with a nut attached, while a screw pulls two pieces together and only the head of the fastener is visible. But I can think of plenty of exceptions such a machine screws.

Are Nails Used in Woodworking?

There is a common misconception among non-woodworkers that we use a lot of nails. Nothing could be further from the truth. In the ten years of projects on this channel, I don’t think I have ever used nails in a project, other than for decorative purposes. Sometimes I use brads for holding boards together while glue dries, but never as a sole means of assembly.

Nails are a pain to hammer in, can bend, and you can easily mar the surface of your project with the hammer head. Not only that, but they don’t hold nearly as well as screws and can work themselves loose.

Parts of a Screw

A screw is made up of 4 components:

- The tip

- The shank

- The threads

- The head

The Tip

Screws used in woodworking will have a pointed tip to help guide the screw into a precise location. Self-drilling screws have a split point that cuts into the wood like a drill bit. Other screws, such as machine screws have no point.

/wood-joinery-types-3536631-v3-5b9827b84cedfd002536486c.png)

The Shank and the Threads

The treads of a screw wrap around the shank. Together, this is the part that drives into the material. The threaded part of some screws stops before it gets to the head, while other screws are fully threaded.

Shanks and threads come in different sizes. The diameter is indicated by a number. The most common wood screws are number 6, 8, and 10, the larger the number the bigger the thickness. I almost always use #8 diameter screws. Longer screws are usually #10s.

In the U.S. threads are sometimes indicated in threads per inch, usually 24 or 32 tpi. These are important to know with machine screws or bolts where you need to get a nut to match. Sometimes wood screws come in coarse or fine threads. Use fine threads for hardwoods and coarse threads for softwoods and plywood.

So when you are reading a box, the first number will tell you the screw diameter. This will sometimes be followed by the threads-per-inch, then then length of the screw.

The Head

There are two components of a screw head. It’s head shape and It’s drive type. Read on to learn about these.

Types of Drives

There are lots and lots of different types of drives, but thankfully, there are just a few common ones you need to know.

Slotted: What is a Flathead Screw?

Slottedscrews are the original method for driving a screw. Like the name implies, it’s just a slot that a flathead screwdriver turns. For this reason, these types of screws are commonly called flathead screws way more often than slotted screws.

Flathead screws require a lot of patience to use and are very difficult to drive with a drill or impact driver. It’s weird how common they still are, still readily available at hardware stores. Basically they suck and I would never recommend them for woodworking with one exception: if you want to make a period piece of furniture with historic accuracy. Other than that, avoid slotted screws whenever possible.

Phillips

When Phillips screws came out in the 1930s, they were a vast improvement over slotted screws. A Phillips head driver will stay in place a lot better, but they still have an annoying tendency to cam-out, or slip when driving the last bit into wood. This can ruin the head and also ruins the driver.I have heard that they were designed to do this in order to prevent over tightening, but I’m not sure if that’s true.

They come in different sizes so always make sure your driver matches and fits well. I really wish Phillips screws would become obsolete, but they are still extremely common in the U.S. the vast majority of screws sold at hardware stores are still Phillips.

Square (Robertson) Drives

Square drives are a huge improvement! They are also called Robertson screws and are most common in Canada. They are definitely harder to find in the U.S. Their square shape greatly reduces, almost eliminating cam-out and driver slipping. Here in the U.S. you will mostly find these in pocket screws.

Star (Torx) Drive

Star drive screws are becoming more and more common in the U.S. and are my absolute favorite type of drive. The star shape virtually eliminates cam-out and the driver almost never slips out. Plus they can accommodate a lot of torque. Usually they are sold on premium quality screws that won’t snap if tightened too much. And when you buy a box, it usually comes with the driver tip you need.

Head Shapes

Like the drive types, there are all kinds of head shapes. Luckily, there are really only two that common in woodworking.

Flathead

This is where the terminology can get a little confusing. It’s easy to confuse a screw with a flad head, and a slotted screw that we often call flathead screws. For woodworking a flathead screw is the most common kind of screw to use. It has a beveled head that seats neatly into the wood, making it flush with the surface

You can just power the screw into the wood to make it flush, but you will get better and cleaner results if you use a countersink bit to drill a pilot hole, or use a countersink to cut the bevels after you drill a pilot hole.

Panhead of Rounded

Panhead or roundheads can have shallow or deep domes. They sit on top of the wood and aren’t used much for woodworking. You will need to use these when attaching some other material to wood…something that you can’t countersink, say metal or plastic.

Types of Screws

Standard Wood Screws

Wood screws are widely available in all home centers and hardware stores and are designed to join two pieces of wood together. They are threaded part of the way and then have a smooth shank at the top. This helps hold the screws in place. They are relatively inexpensive and come an all kinds of diameters and head shapes. You will usually want to use the ones with the tapered heads. Unfortunately, in the U.S., most woodscrews are still only available with Phillips heads instead of star or square drives.

Standard wood screw

Drywall Screws

A lot of woodworkers use drywall screws, mostly for shop projects and jigs. They are inexpensive, usually cheaper than wood screws and easy to find just about anywhere. They have thinner shanks than wood screws, usually about equal to a #6 screw and threads that run the entire length of the screw. Because of their thinness they are really brittle. Especially ff you are drilling into hardwood, they are really prone to snapping, but I’ve had this frustrating experience with using them for 2x4s too. Like wood screws, in the U.S. the heads are almost always Phillips. Also, the heads have a bugle shape to reduce tearing the paper on drywall. They don’t match the beveled shape of a countersink. In general, I don’t recommend using drywall screws for woodworking projects.

What’s the difference between a drywall screw and a wood screw?

Multi-purpose (production) screws

Production or Multi-purpose screws are my absolute favorite types of screws. Common brands include Spax or GRK. These screws are made with hardened steel and are incredibly strong. I don’t think I’ve ever had any break. They have self-drilling points that eliminate the need for a pilot hole, but I would still pre-drill for critical pieces. Especially near the ends of boards to prevent splitting.

The best part is that they come in star or square drives so your driver stays in place and won’t slip out like with Phillips. Plus, when you buy a box, it comes with a driver bit. There is really only a single drawback to using these: they are expensive. Maybe twice as much as regular wood screws. And while my Mere Mortals philosophy is always to be frugal, this is one instance where I believe it’s worth spending the extra money. The amount of time and frustration these types of screws save is enormous.

If you’ve never used multi-purpose or Spax screws, just get one box and try them out. I guarantee, you will wonder why you didn’t try them sooner!

Other Types of Screws

Deck Screws

If you are building outdoor projects, use deck screws. They are made of hardened steel and have a corrosion resistant coating.

Stainless Steel Screw

For even better corrosion resistance, especially on boats and in salty marine environments, you can use stainless steel screws. While they offer the best protection from the weather, they are not as strong as deck screws and are very expensive.

Pocket Screw

Pocket screws are self drilling and have a wide head that grabs the flat shoulder made by drilling pocket holes. If you use regular wood screws with pocket holes, they may drive all the way through, or possibly split the wood. I use the Kreg pocket screws, but you might be able to substitute pan head screws. The Kreg screws have a square drive which makes them really easy to seat. Watch my pocket hole basics video to learn a lot more about pocket hole joinery.

Machine Screws

Machine screws have no points and are intended to use in holes that are already tapped or with a nut. They are threaded along the entire shaft are sold in threads per inch. When you buy them, make sure the nuts’ threads match. You may occasionally need machine screws to fasten a couple boards together, but they aren’t common in woodworking.

Sheet Metal Screw

Usually, sheet metal screws are tiny with a sharp point intended for piercing and driving into sheet metal. Think of heating ducts for instance. They usually have pan heads and will probably work as a wood screw if you need a substitute.

And there’s a basic look at the various types of screws. While there are a lot of choices available, there are only a few different types of screws a woodworker will ever need. Know what kind you need for your project before going to the hardware store or home center. Just buy what you need. I don’t recommend stocking up on anything other than #8 1-¼” screws. I always like to have these on hand.

Woodworking is all about shaping wood. While there are a wide variety of ways in which we shape that wood, they can be broken down into two basic categories: cutting wood to remove parts and attaching pieces together. Within each of those two categories, there are several different ways of accomplishing most woodworking tasks.

For the most part, woodworking today is done with power tools; but that wasn’t always the case. If we go back 100 years, there were no electric power tools to use. While the sawmill goes all the way back to 1594, sawmills were few and far between. There was no chance that someone would have their own. The first handheld electric drill, the most common electric power tool there is, wasn’t invented until the late 1800s and was first only used in factories.

Today, we have a multitude of different power tools, allowing us to do a wide variety of woodworking tasks. The problem, for many of us, is that there are too many tools available for what our budget can support. We end up buying the tools we need the most and finding ways of making do for everything else.

This is why it’s valuable to know alternative ways of doing things. Those alternative ways might involve using other types of power tools to complete the task or they might be the methods that our forefathers used, working with hand tools, rather than power tools. Either way, they’re worth having in our bag of tricks.

The Rapid Cutting Router

For this article, we’re going to concentrate on alternatives for shaping which is normally done with a router. Routers are high-speed tools, in which a motor turns a bit, which sticks down through a base at 90 degrees. The height of the bit can be adjusted, as compared to the base, affecting exactly where on the workpiece the bit is cutting. A variety of bit shapes are available.

Routers can be handheld, with the base placed on the workpiece or they can be mounted upside-down in a router table, allowing the workpiece to be run across the router bit. Generally speaking, the router is used without the table for larger workpieces and mounted to a table for smaller ones. Some woodworkers have two routers, allowing them to leave one mounted to their router table.

A router is a handy tool to have, being used for cutting grooves (properly called rabbeting), cutting slots in boards, such as for hanging them, trimming the edge of laminate, and cutting various types of tongue and groove joints for putting pieces together. They are also used for rounding or chamfering the edges of tabletops, as well as cutting molding edges directly into those edges.

Alternative Ways to Cut Grooves (Rabbeting)

Rabbeting means to cut a groove in a board. This groove might be in the edge of the board, which is a useful way of connecting boards at corners or it might be in the middle, such as for a drawer slide. In either case, the most common tool for cutting these grooves is the router. But what do you do if you don’t have a router available to cut a groove in your workpiece?

Regardless of which method you’re going to use to cut the rabbet, you’re always going to want to start by marking exactly where you’d like to make a channel. The old rule of “measure twice, cut once” applies just as well here, as it does anywhere else. Be sure to use a straight-edge when marking to cut a straight line, not just a convenient board. It’s amazing how many boards come from the sawmill with edges you can’t count on.

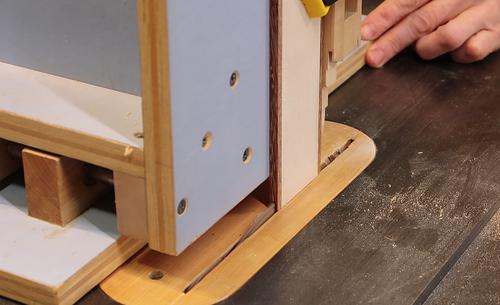

Table Saw Method

Typically, grooves cut into wood on a table saw are cut using a dado blade. There are several types of these, including one where the blade wobbles side to side, cutting out the groove and one which is essentially a stack of blades. Both types can be adjusted for the width of groove that is wanted and both work, although the surface finish provided by the wobbling blade style is not as good as that provided by the stack of blades.

When cutting a dado or rabbet on a table saw, always make a test cut, as both the width and depth of these cuts can turn out to be different than what you expect. You should also measure the distance between the edge of the saw blade and your fence with a tape measure, as the built-in gauge for your fence will not be accurate with these blades installed.

If you don’t have a dado blade for cutting grooves, you can still cut them on a table saw, using the standard blade. For most table saw blades, the kerf (width of cut made by the blade) is 1/8”, although there are some “narrow kerf” blades which only cut out a tenth of an inch.

To make a wider than 1/8” groove in the wood, all that you need to do is make a series of cuts which overlap each other, moving the workpiece between each cut. If your groove travels the length of the workpiece, this can be accomplished by moving the table saw’s table. If it runs across the width of the board, you’ll need to use the miter gauge, moving the workpiece slightly between cuts.

Always make a test cut to double check the depth your blade is cutting, whenever making a cut on a table saw that does not go all the way through the board. While you should be able to measure the height of the highest tooth off the table and determine this, that measurement usually isn’t accurate enough.

Dremel Tool Method

You can cut a channel in wood with a Dremel tool or similar tool; however it is nearly impossible to get a clean cut in this manner. You can improve how clean the edges of your cut are by first cutting them with a utility knife. This will also help to prevent splintering of the edge.

Using a Dremel tool works best for short cuts, as the rotary bit on this tool is small and long cuts can be time consuming. Be sure that the bit on the tool will go to the correct depth, then get to work, following your line. You’ll finish up eventually!

Rabbeting Plane

Before the existence of routers and table saws, woodworkers made grooves in wood parts with a rabbeting plane. This can either be a wood or metal bodied plane, where the plane’s body is exactly the same width as the blade. Rabbeting planes come in a variety of different widths, up to one inch, to match the most common groove sizes used.

Rabbeting planes can be used in the middle of a board or at the edge. They can be used with the grain or for crosscutting. The major difference between crosscutting and cutting with the grain, is that you need to make sure that you use a thinner depth of cut for a crosscut, than you would when cutting with the grain.

Some rabbeting planes come with a fence, which allows you to set the width of a rabbet, when making the rabbet at the edge; but most don’t. Professionals get by without a fence, by cutting a narrow groove with a sharp knife, at the edge of where they want to make their cut. This groove can then be used to guide the plane.

If you’re not that skilled, an alternative is to clamp a straight edge, metal-bodied level or straight board across the piece you are trying to cut the groove in, using it as a fence, once you get a little bit of the groove cut, you can remove the fence, as the plane will ride in its own groove.

How To Make Square Slot In Wood Dowels

Chisel Method

If you’re completely desperate and have no power tools, you can always cut a groove the old-fashioned way by using a chisel. This was the normal way of cutting a groove for centuries, especially for apprentice woodworkers, who didn’t have a rabbet plane to use.

As with the other methods, start out by marking where you want to cut your groove, marking both edges of the cut. Then use a back saw to cut along those lines, to the depth that you want to make your groove. Be careful on this, as it is extremely easy to get the ends of the cuts to the full depth, without getting the middle cut that deep.

With the sides of the groove cut out, it is an easy task to cut out the material in the groove with a chisel. Use a chisel that is as close to the width of the groove as possible, without going too wide. As you reach the bottom of the groove, be careful not to overcut.

How to Make Rounded and Chamfered Edges on Wood without a Router

A router is by far the best tool for modifying the edges on wood, whether that modification is creating a rounded edge, a chamfer, a beaded edge or some other type of molded edge. Many of the wide variety of router bits on the market are specifically designed for these purposes. But what do you do, if you don’t have a router available to do this type of work?

A lot depends on the kind of edge you’re trying to make. Obviously, some are more difficult to accomplish than others. Much of this involves using various types of wood planes. But before routers, planes were one of the woodworker’s top tools. Most would have a large number of planes, many of which they had made themselves and each of which had a specific purpose.

Rounding and Chamfering with a Plane

If you have a standard wood plane, what’s known as a “Jack plane” or “bench plane,” rounding and chamfering edges is easy. All you have to do is to run the plane down the corner of the board a number of times, until you get the edge you want. For a chamfer, you’ll need to hold that plane at a consistent 45 degree angle for all the strokes and to round it; you’ll want to vary the angle. To finish off the rounded edge, sand out the flats created by planning.

Always use a plane following the direction of the grain, when planning the long edge of a board. You want the grain moving up and towards the edge, as it moves away from you. Otherwise, the plane’s blade can catch in the grain, tearing out chunks of the wood, rather than shaping it the way you want.

For rounding and chamfering the ends of the board, where you are cutting across the grain, you’ll want to use a block plane, rather than the planes mentioned earlier. These are smaller planes, but the important difference is that the blade is set at a 35 degree angle to the surface, making it easier for them to cut across the grain. Always ensure that the blade is sharp, so that it will cut through the grain.

Rounding Edges with a Sander

Another option, which allows you to use a power tool, rather than working with hand tools, is to use a vibratory or random orbital sander. This will not provide you with as clean and crisp a rounded edge; but rather, an edge which looks worn, especially at the corners. Work one edge at a time, gradually removing wood, until you have created a rounded profile that looks good to you. It’s tough to be precise with this, but the finished results are visually interesting and perfect for rustic furniture and woodwork.

Of course, the same thing can be done sanding the wood by hand, although it is much more work.

Using Molding Planes

A moment ago I mentioned that carpenters and cabinet makers used to use molding planes to cut profiles in the edges of wood, before the router was invented. These planes were used for both creating fancy edges on the wood of cabinetry and furniture and to make architectural molding. Each particular profile the woodworker would want to cut required its own special plane.

The shoe of these planes would look like a mold of the profile to be cut and the blade would be ground, filed and sharpened to match that profile. In a carpentry or cabinet making shop, they will make their planes off a “mother plane” which is the reverse of what they are trying to create. The mother plane would cut the profile into the shoe of the planes they would use, then they would grind the blade to match that shoe.

You can find these molding planes for a very reasonable price in many antique shops. While they might need some cleaning up and sharpening, most are in fairly reasonable condition. Just make sure that the shoe of the plane isn’t split or have missing pieces and that the blade matches the contour of the shoe. They sometimes get mixed up.

How To Make Square Slot In Wood Lathe

Molding planes are used just about like you’re trying to plane the edge of the board, with the exception that they will make a contour, rather than making the edge of the board flat and smooth.

Molding with a Scratch Stock

A simple tool, called the scratch stock, was used in cabinet shops, when only a small amount of a particular molded edge was needed, such as a triple beaded edge for the top of a dresser. This tool consisted of a clamp to hold the blade, with a lip to align it with the edge of the board to be molded. There was no shaped shoe, like on a molding plane.

Blades for the scratch stock were usually ground from pieces of old, broken bandsaw blades. In the photo above, the author used a broken sawzall blade for the scratch stock. The working end of this blade is not visible in the photo, as it sticks out underneath the tool, but it is ground to provide a triple bead on the edge of a board. The end sticking up has been ground to provide a different profile. All that would be needed to use that end would be to reverse it in the tool handle.

How To Make Square Slot In Wood Floors

How to Cut a Slot in Wood

Another task that is often done with a router is cutting slots. This differs from cutting a groove in that the slot does not go the full width of the board. Different types of slots are cut for different purposes. There are a few ways to cut a slot in wood without a router. The method you choose depends on the type of slot you’d like to make, as well as on the tools you happen to have on hand.

Keyhole Slot

Keyhole slots are used typically for hanging finished work on the wall. There will be an opening for the head of a screw to go through, along with a slot that is small enough that the screw head cannot pass through it. Keyhole slots can either be cut all the way through a board forming the back of the project or cut into it, depending on the thickness of the board.

These slots are normally cut with a special bit on a router, using a fence, with the router mounted in a router table, to keep the slot straight. But they were in use long before the router or the router table were invented.

Start by marking a line, showing where the slot is going to go and which end the larger hole is on. Drill the clearance hole that the screw head has to pass through at the appropriate end of the line. This is normally about 1/32” larger than the diameter of the screw head. Then drill a hole the same diameter as the slot, at the other end of your line. This is normally 1/32” wider than the screw threads, what’s referred to as the “major diameter” of the screw.

Draw two parallel lines, the width of the smaller hole, from that hole to the larger hole, ensuring that they are centered on the larger hole. Cut the material between the two holes with a keyhole saw. This is a small saw, with a very narrow blade and a point on the end.

Another way of cutting out that material is to drill a series of holes, following the line, with the smaller size drill bit. Then, cut out the remaining material with a small chisel.

Cutting Slots in Wood with a Jigsaw

If you want to cut an open slot in wood, you might find that a jigsaw does the trick. Start by drilling two holes at each end of the desired slot. You’ll need to make sure that at least one hole is large enough to accommodate the jigsaw blade. Cut the slot, working carefully and moving slowly.

Cut a Slot in Wood with a Circular Saw

It’s normally not recommended to make plunge cuts with a circular saw, for safety reasons, but many woodworkers do it anyway. It’s definitely safer to make a plunge cut with a circular saw than it is to make the same cut with a table saw. For safety, before you get started, be sure that you have a good sharp blade on your circular saw. Be sure to wear the proper eye and ear protection for this task, and clamp your wood into position before you get started. Stand to the side, not behind the saw.

Raise your blade guard and set the blade to the proper depth, just a bare fraction of an inch deeper than the depth of the wood.

Line up the blade with your guide line. Tip your saw up and activate the blade. Once it’s at full speed, double-check to ensure that you’re still over your guide line. Plunge your blade slowly into the wood, release your guard, and then make your cut. It’s a very good idea to practice this technique on scrap wood before moving on to anything important.